From Prosperity To Fracture And Hopes For Renewal.

Disclaimer.

This article reflects on Australia’s economic and industrial history through metaphor and observation.

It is general in nature and is written for educational and reflective purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or business advice.

The perspectives offered are based on publicly available historical data and should not be interpreted as recommendations.

Views, thoughts, opinions and ideas expressed are those of the Author only and readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and seek professional guidance tailored to their circumstances.

Article Summary.

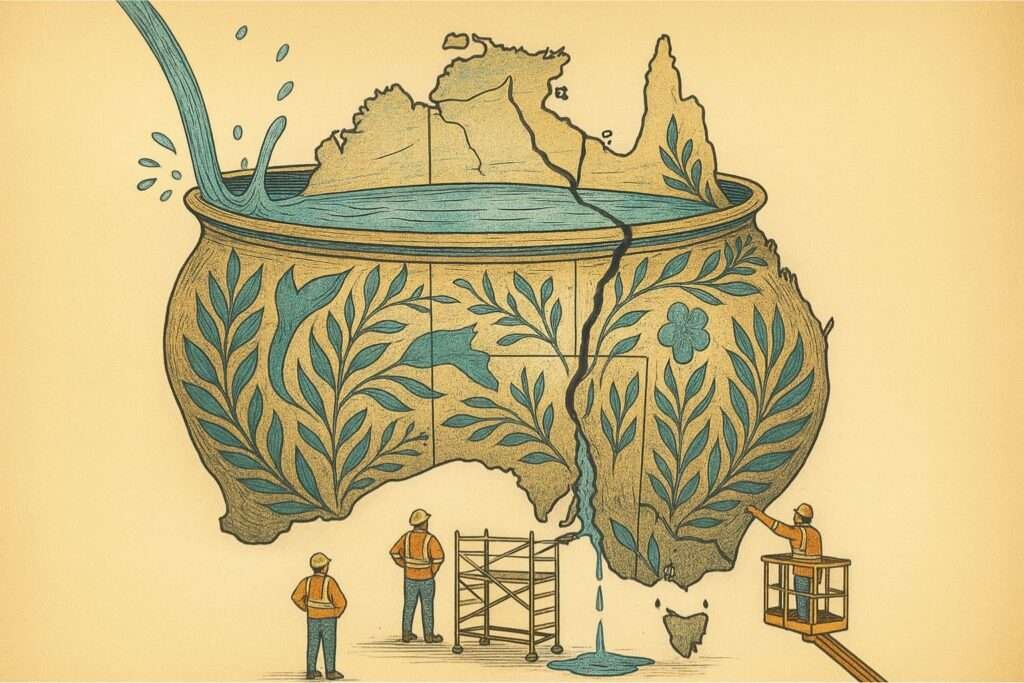

Australia’s economic journey over the past six decades resembles a ceramic vessel: once whole, radiant with industrial strength and now etched with fractures left by global competition, technological disruption and structural change.

Manufacturing, which contributed nearly 25% of GDP in the 1960s, has diminished to one of the lowest shares in the OECD, reshaping not only the economy but also the nation’s sense of prosperity, identity, and collective memory.

Through the metaphor of the cracked vessel, this article asks whether these fractures signify decline or transformation—whether the light that now filters through represents loss or renewal. It is not a tale of collapse alone, but of metamorphosis: a story of how nations, like brands, must reconcile heritage with evolution, and how imperfection itself can become a source of strength.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1) Prosperity’s Changing Face: Australia’s economy has shifted from the visible prosperity of manufacturing, 25% of GDP in the 1960s to the more abstract wealth of services, mining, and digital industries. Prosperity once seen and touched is now measured and managed.

2) The Fracture Timeline: The cracks appeared in stages: oil shocks and tariff cuts in the 1970s–80s, plant closures in the 1990s–2000s and the automotive industry’s final exit by 2017. Each fracture reshaped not just the economy, but the nation’s sense of itself.

3) Generational Displacement: Three generations embody the shift: the factory worker who built with pride, the service worker who managed with uncertainty, and the digital worker who creates value in code. Each lives in a different relationship to prosperity.

4) The Authenticity Paradox: Like a brand that falters when promise diverges from reality, Australia’s industrial story fractured when the myth of self-sufficiency no longer matched lived experience. The result: a lingering crisis of identity that still shapes politics and culture.

5) Renewal Through Imperfection: Light does shine through the cracks. Advanced manufacturing niches, creative industries, agriculture, and technology sectors hint at renewal—not a return to industrial glory, but a reimagining of prosperity that embraces transformation rather than restoration.

Table of Contents.

1. Introduction: The Vessel in Our Hands

2. The Vessel’s Prime: Manufacturing’s Golden Age (1960s)

3. The First Fine Lines: Early Tremors (1970s–1980s)

4. The Sound of Cracking: Structural Shifts (1990s–2000s)

5. The Visible Cracks: Industrial Exodus (2010s–2025)

6. The Light Through the Cracks: Signs of Renewal

7. The Nature of Prosperity: Then and Now

8. What Cracks Reveal About Identity and Brand

9. Questions Without Ultimatums

10. Conclusion: The Vessel We Carry Forward.

11. Bibliography.

1. Introduction: The Vessel in Our Hands.

Picture a ceramic vessel, fresh from the kiln. Its surface gleams with promise, smooth to the touch, unblemished, substantial in your hands.

You can trace its contours, feel the weight of what it holds, and know with certainty its purpose and worth.

Now imagine that same vessel decades later. Fine lines web across its surface. Some cracks run deep, others appear only in certain light.

The glaze has dulled, chipped in places and yet it still holds together.

Look closely and you may see something remarkable: where the fractures run deepest, light finds a way through.

The vessel has become what it never was when whole, a map of its own history, a testament to what it has carried, endured, and transformed into.

This is the story of Australia as vessel: a meditation on how a nation’s economic identity fractures, adapts, and reveals something unexpected about the nature of value itself.

It is not simply a story of decline, though decline plays its part.

Nor is it a straightforward tale of renewal, though renewal emerges in surprising places.

It is, instead, an exploration of what happens when the container of national prosperity begins to crack, when the story a country tells itself no longer matches the reflection in the mirror.

When a vessel cracks, does it lose its value?

Or…… does it finally start to tell its truest story?

2. The Vessel's Prime: Manufacturing's Golden Age (1960s).

Australia’s 1960s manufacturing era marked an economic high point unmatched before or since.

Manufacturing contributed nearly 30% of GDP and employed about one-third of the national workforce, making it the beating heart of Australian prosperity.

With GDP growth averaging over 5% annually across the decade, the country achieved a rare mix of rising incomes, expanding middle-class security, and industrial innovation.

2.1 Industrial Power and National Confidence.

Factories dominated Melbourne’s west, Sydney’s inner industrial belt, Adelaide’s north, and Brisbane’s southern corridor, landscapes filled with furnaces, presses, foundries, and conveyor belts.

It was an era of visible productivity: the clang of steel at BHP’s Port Kembla and Newcastle plants, the hum of looms in mills from Brunswick to Footscray and the steady rumble of trucks ferrying components across a rapidly modernising nation.

By 1967, Australia was the largest producer and consumer per capita of galvanised steel and firms like Lysaght and BHP were expanding rapidly, developing products like Colorbond steel and modern rolling mills at Whyalla and Western Port.

The country’s steel capacity supported construction, shipbuilding, and car manufacturing pillars of the era’s material optimism.

2.2 The Great Australian Car Boom.

Few symbols captured the energy of the 1960s more vividly than the car industry. At its heart stood Holden, Australia’s industrial heart, embodying the confidence, craftsmanship and optimism of a nation that built for itself.

By the mid‑1960s, one in sixteen Australians worked in the manufacture, distribution, or servicing of motor vehicles.

This was not just an economic statistic; it was a social identity.

The car industry touched nearly every household, directly or indirectly and gave shape to the rhythms of suburban life.

At its employment peak, Holden counted around 24,000 workers across seven plants, Fishermans Bend, Dandenong, Pagewood, Acacia Ridge, Woodville, Elizabeth, and Mosman Park.

The Elizabeth plant, opened in 1960, stood as a monument to post‑war optimism and modern industrial design.

Thousands of new migrants built their lives around its factory floor, their labour weaving into the fabric of a new, confident Australia.

In 1962, Holden celebrated the production of its one‑millionth vehicle, an EJ Premier sedan, the first time any carmaker in Australia had reached such a milestone.

It was more than a number: it symbolised our national maturity, a declaration that Australia had joined the ranks of advanced industrial nations.

By 1966, the HR series arrived with refreshed bodywork and the now‑legendary “red” six‑cylinder engines (161 and 186).

Produced in more than 252,000 units, the HR became Holden’s most popular model to date, dominating suburban driveways.

Reliable yet stylish, practical yet aspirational, it offered both transport and pride of ownership. With its X2 performance option and Powerglide automatic, the HR was as much a statement as it was a car.

Then, in May 1967, Holden stepped into the compact segment with the HB Torana. Derived from Britain’s Vauxhall Viva but adapted for Australian conditions, it seemed at first a pragmatic addition, a smaller, affordable option alongside the family sedans.

Yet what General Motors‑Holden could never have foreseen was how deeply the Torana would embed itself in Australian culture.

What began as a modest compact evolved into a nameplate that inspired fierce loyalty, motorsport glory, and a mythology all its own.

Decades later, the Torana is not just remembered, it’s revered.

Collectors now pay extraordinary sums for pristine examples, with perfect‑condition units commanding six‑figure prices at auction.

In late 2020, a 1977 Holden Torana A9X raced by John Harvey of the Holden Dealer Team sold for $910,000, making it one of the most expensive Holdens ever auctioned.

In 2024, a rare GMP&A A9X shell, one of only 33 lightweight race‑specification bodies, fetched over $800,000, underlining the Torana’s enduring rarity and cultural weight.

The little car that once seemed a cautious experiment in the 60’s became one of the most sought‑after symbols of Australia’s golden age of manufacturing.

The EH Holden, produced from 1963 to 1965, had already set sales records with 256,959 units and introduced the “red” engine that became central to Holden’s identity. But 1968 was the watershed.

The HK series introduced the Kingswood nameplate and expanded Holden’s reach into both luxury and performance markets.

That July, the Monaro arrived, a sleek, pillarless coupe that Australians instantly claimed as their own. In GTS 327 form, it became the nation’s first true muscle car, winning admiration on the street and trophies on the track.

The late 1960s marked the high tide of Australian automotive production. Holden, Ford, and Chrysler collectively turned out hundreds of thousands of vehicles each year, designed, assembled, and built locally with substantial Australian content.

The rivalry between the HK Kingswood and Monaro, the Ford Falcon, and the Chrysler Valiant defined not just the nation’s roads, but its imagination.

By the decade’s end, Holden had produced its two‑millionth car, employed tens of thousands directly, and sustained many more through suppliers, transport, and dealerships.

The car was more than a product, it was proof our industrial capacity, ambition and confidence.

3. The First Fine Lines: Early Tremors (1970s–1980s).

Vessels, like economies, exist within shifting environments.

The 1970s brought the first hairline fractures, so fine you might miss them in a certain light, but present nonetheless.

The 1973 oil shock rippled through industrial economies worldwide.

Energy costs spiked and supply chains convulsed. For the first time in a generation, the certainty of uninterrupted growth wavered.

Australia, insulated by distance and protected industries, felt the tremor but did not yet crack. The factories continued their rhythm, though the hum carried a new, anxious pitch.

Then came the 1980s and a fundamental reshaping. Tariff walls, long the protective shell of Australian manufacturing, were systematically dismantled.

The floating of the dollar in 1983 exposed the economy to global currency flows. Financial deregulation opened doors to international capital.

The old certainties of protection and isolation gave way to the new mantras of efficiency and competition.

The father on the line noticed the change:

· Perhaps his shift was cut back.

· Perhaps the company announced restructuring.

· Perhaps colleagues were laid off, and those who remained worked harder, faster, with less certainty about next year.

The factory still stood, the machines still ran, the paychecks still arrived, but something beneath the surface had shifted.

The ground no longer felt as solid.

These were the years when the first fine lines appeared on the vessel’s surface. Not breaks, not yet, just stress marks, points where pressure began to concentrate, where the story of self-sufficient prosperity and the reality of global competition slowly, inevitably diverged.

The vessel still held, but those who listened closely could hear a faint, brittle edge in its sound.

4. The Sound of Cracking: Structural Shifts (1990s–2000s).

The 1990s brought not whispers but declarations. Factory closures no longer shocked; they became routine headlines.

· Textile mills fell silent as cheaper imports flooded in.

· Electronics manufacturing migrated to Southeast Asia.

The language of business shifted, outsourcing, global supply chains, core competencies and lean operations. Each phrase was a euphemism for the same reality: the work was leaving our shores.

This was the era of the quiet sigh, the collective exhalation of communities built around industries now methodically packing up and departing.

A plant in Geelong shuttered. A textile mill in Wollongong ceased operations. A component supplier in Adelaide closed its doors.

Each closure was justified in the rational language of economics—comparative advantage, labour costs, productivity differentials.

Yet it was felt in the visceral language of loss: empty carparks, silent machines, families left uncertain

The son of the factory worker found himself in a different world.

· Services were hiring.

· Call centres expanded.

· Finance and retail grew.

These were jobs, sure and some paid very well. However, the relationship between labour and output had changed.

You sold insurance, processed claims, managed accounts and at the end of the day, what had you made? What could you point to and say, “I built that”?

For generations, the pride of work was bound to the tangible.

A factory worker could walk past a bridge and know the steel beneath its span once passed through the building he works in.

A tradies could see a car roll down the street and recognise the hum of an engine he had helped assemble. These were not just products; they were proof. Proof of skill, of contribution and of belonging.

Service work that replaced ‘making work’, by contrast, often leaves no such trace. The labour is real, the value undeniable, but it is abstract, numbers in a ledger, data in a system, outcomes that vanish into the ether of the digital.

Neuroscience tells us why this feels different: our brains are wired to reward the act of shaping the physical world around us.

The feedback loop of hand, eye, and mind working together releases a satisfaction that no spreadsheet can replicate.

And there is something older still, something almost mythical. Across cultures, creation stories begin with hands shaping clay, weaving fabric, carving wood.

To make is to echo the act of creation itself, to leave behind an object that carries both function and memory.

When that link between labour and object is severed, prosperity becomes harder to see, harder to touch, harder to believe in.

This was the fracture of the 1990s and 2000s: prosperity remained, but it grew less tangible, less embodied. The vessel still held, but the substance inside no longer felt like something you could grasp.

Prosperity was becoming more abstract, less tangible, hard to visualize, even harder to locate in the physical world.

Manufacturing’s share of GDP slid steadily downward, below 15%, then below 12%. Yet paradoxically, the economy grew.

Services expanded. The mining boom of the 2000s delivered a different kind of prosperity, spectacular in scale, concentrated in resources, but employing far fewer people than the factories ever had.

The vessel still held, but the cracks were no longer hairline. They had widened, deepened, become impossible to ignore.

In brand terms, this was the danger zone.

The story, Australia as industrial powerhouse, as nation of makers, was diverging rapidly from lived experience.

When a brand’s promise and its delivery separate, erosion begins.

Not catastrophic at first, but steady, cumulative, corrosive.

The vessel was cracking audibly now, and the sound was unmistakable, like porcelain under strain, brittle and echoing through every community that once thrived on the hum of machines.

5. The Visible Cracks: Industrial Exodus (2010s–2025).

By 2017, it was finished. The last automotive assembly plant closed its doors.

Ford, Holden, Toyota, all gone, taking with them not just jobs, but a century of industrial identity.

Manufacturing’s share of GDP had collapsed to around 6%, among the lowest in the OECD. The transformation was complete.

Drive today through Melbourne’s western suburbs or Adelaide’s northern industrial zones and you see the archaeology of that transformation.

Steel mills reborn as apartment complexes, their girders preserved as architectural features, half irony, half nostalgia I suppose.

Factory floors converted into boutique shopping precincts. Warehouses repurposed as artisan breweries and co‑working lofts. The buildings remained but their purpose had metamorphosed entirely.

The granddaughter of the factory worker now writes software code for a tech company. Her factory floor is the lines of code that stream across her laptop screen. She often works remotely from home, creating products that have no physical form, generating value that exists entirely in ones and zeros.

By most measures she is prosperous, probably earning much more than her grandfather ever did, adjusted for inflation.

Yet the nature of that prosperity is fundamentally different.

· You cannot touch what she makes.

· You cannot walk through a factory and see her labour transformed into a product that’s getting loaded onto a truck.

Here the vessel shows its deepest cracks. It’s not broken as Australia’s economy remains robust, its GDP per capita is high, its standard of living enviable.

But fractured, it certainly is.

The coherent story of tangible, broadly shared, manufacturing‑based prosperity has given way to something more complex, more uneven, harder to narrate with confidence.

The mining and energy sectors have expanded dramatically. Australia exports iron ore, coal, and natural gas on a massive scale, generating extraordinary wealth.

But mining employs less than 2% of the workforce. Finance, insurance, and business services have grown, but they concentrate prosperity in ways manufacturing never did.

The digital economy creates millionaires and billionaires, but its benefits accrue unevenly, unpredictably.

The vessel brimmed with resource wealth, but its contents pooled unevenly, leaving many hands dry.

The cracks are visible now and unmistakable.

The vessel still holds, but it contains a different kind of prosperity, less visible, less evenly distributed, less tangibly connected to the labour that generates it. The question is no longer whether the vessel is cracked. The question is what the cracks mean.

6. The Light Through the Cracks: Signs of Renewal.

When light strikes a cracked vessel, it does not restore the surface to wholeness. It does something subtler: it filters through the fractures, catching the eye in unexpected ways.

The cracks do not erase or hide the vessel’s history, they reveal it.

Australia’s economy today shows such fractured illumination.

The great factories are gone and with them the broad, tangible prosperity they once spread.

Yet in the spaces left behind, smaller forms of making persist.

Advanced manufacturing survives in niches, precision aerospace parts, medical devices, defence contracts—industries that employ fewer people but demand higher skill.

Agriculture, too, has adapted, blending tradition with technology to remain globally competitive. Also, in the creative industries, film, design, gaming, digital media, Australia continues to produce, though in ways the old factories never imagined.

These are not replacements for the scale of the past. They are footholds, fragile lights filtering through the cracks.

They remind us that making still matters, even if the objects of labour are fewer, more specialised, or intangible.

The vessel is fractured, yes. But perhaps fractures create possibilities that smooth surfaces never could.

Perhaps the cracks, painful as they are, allow us to see value differently, to recognise that prosperity is not only measured in volume, but in meaning.

The question is whether we can learn to live with a vessel that no longer gleams with industrial certainty, but instead carries its history openly, its light refracted through the very lines of its breaking.

7. The Nature of Prosperity: Then and Now.

There is a profound difference between the prosperity of the 1960s and that of 2025, one that transcends statistics. It is a difference of texture, of visibility, of how prosperity is felt and understood.

In the 1960s, prosperity was broad and unmistakable. You knew someone who knew someone who worked at the plant.

Entire suburbs existed because the factory was there; communities organised themselves around shift patterns, union halls, and the shared rhythm of making.

Growth was visible in new houses rising on the edge of town, in cars gleaming in driveways, in bridges and schools built with local steel.

The connection between national prosperity and personal experience was direct, legible, and deeply felt.

Today’s prosperity is more abstract, more concentrated, less visible to the casual eye. Wealth is less made and more managed.

A mining executive in Perth oversees billions in exports but employs thousands rather than hundreds of thousands.

A software engineer in Sydney creates an app used by millions, generating personal wealth but leaving little physical trace.

An investment banker in Melbourne moves capital across borders, transactions that register in national accounts but not in neighbourhood employment.

This is not to say today’s prosperity is less real. By many measures, median income, access to goods and technological capability, Australians live better than our 1960s counterparts.

Yet the experience of prosperity has changed. It feels more precarious, even when the data suggests stability.

It feels more uneven, even when inequality metrics complicate the story.

It feels less secure, even for those who are objectively well-off.

The psychological impact is profound. In the 1960s, you could see the machinery of prosperity. You could intuitively grasp how your labour connected to national success.

Today, that connection is opaque. How does a call centre shift, a consultancy project, or a digital marketing campaign translate into national prosperity?

The chain of causation is longer, more complex, less emotionally satisfying.

This is the deepest crack in the vessel: not the economic transformation itself, but the rupture in our collective understanding of how prosperity is created, distributed, and experienced.

We once lived in an economy where prosperity was tangible and security broadly shared. Now we inhabit one where prosperity is abstract, security is concentrated, and the link between work and national success is mediated by global systems few can fully grasp.

8. What Cracks Reveal About Identity and Brand.

If nations are, in some sense, brands—collections of stories, associations, and promises, then Australia’s economic transformation offers a stark lesson in what happens when a brand’s narrative fractures.

The manufacturing era gave Australia a clear, emotionally resonant brand story: the land of the “fair go,” where honest work in tangible industries produced broadly shared prosperity.

This story aligned internal identity with external promise. It was coherent, compelling and crucially, it matched lived experience.

When story and reality align, brands generate mythic loyalty: allegiance that transcends rational calculation.

But brands fracture when promise diverges from experience. As manufacturing declined, the old story persisted even as reality shifted.

The nation still told itself it was a place of makers and shared prosperity, even as fewer people made things and prosperity grew abstract and concentrated. The vessel cracked not because the economy collapsed, but because the narrative could not adapt quickly enough to the transformation.

This reveals something essential about identity in times of transition.

Narratives are not decorative, they are load-bearing structures. When they crack, societies become unmoored and politics become volatile.

Nostalgia gains power. The promise of restoration, of making the vessel whole again, becomes emotionally irresistible, even when economically impossible.

Yet cracks also create opportunities, for they force honesty. They demand new stories, because just as necessity is the mother of invention, so too do fractures in the vessel compel reinvention.

A vessel cannot pretend to be whole once broken, but it can embrace its fractures as character/features, not flaws.

This is the work of mythic reframing: to acknowledge transformation, to honour what was lost, and to find meaning in what emerges

Australia’s challenge now is narrative as much as economic.

Can a new story arise that is as emotionally compelling as the old ones?

Can abstract, service-based, digitally mediated prosperity generate the same sense of collective purpose that tangible manufacturing once provided?

Can the nation embrace being a cracked vessel, finding beauty, not just loss, in that condition?

These are not questions with easy answers but they are the questions that matter most.

Economic transformations require not only new industries, but new stories—stories that connect individual experience to collective purpose, that restore coherence, that allow a society to see itself whole, even through its cracks.

9. Questions Without Ultimatums.

This is the point where

observation yields to reflection, where the chronicler’s role ends and the

reader’s work begins.

The story of Australia’s

economic transformation, of the vessel cracking, of prosperity changing its

nature, of identity fracturing and reforming does not resolve into neat

conclusions or obvious prescriptions.

Instead, it leaves us with

questions. Not puzzles demanding single answers, but invitations to sit with

complexity:

1.

Did we trade one kind of

prosperity for another, or did we lose something irretrievable while gaining

something incomparable? The statistics suggest material gain. The emotional

texture suggests profound loss. Perhaps both are true, and the work is learning

to hold that paradox without forcing resolution.

2.

Is a cracked vessel less

valuable, or does it tell a richer, more honest story? The pristine vessel is

beautiful in its perfection, but reveals nothing of its journey. The fractured

vessel bears the map of its history, wears its survival as testimony. Value may

depend on what we seek: utility or meaning, function or story.

3.

Can prosperity that is

abstract, digital, and unevenly distributed generate the same social cohesion

as prosperity that was tangible, industrial, and broadly shared? Or do we need

new forms of connection, new ways of experiencing collective purpose, new

narratives that make sense of economic success in a service and information

economy?

4.

When industries decline and

communities transform, what do we owe those who bore the cost of

transformation? Recognition? Compensation? Inclusion in the national story? Or

is economic change simply something societies must endure, with winners and

losers as inevitable by-products?

5.

If the old story no longer

fits, what new story can be as compelling? Can we create a narrative of

Australian identity that embraces advanced manufacturing, digital innovation,

and cultural creativity with the same emotional resonance that the old industrial

narrative once commanded?

These questions have no

definitive answers and perhaps that is appropriate.

The cracked vessel is not a problem to be solved but a condition to be understood, even honoured.

The light shining through the cracks is not a single beam but a spectrum, revealing different possibilities depending on angle and perspective.

10. Conclusion.

Return, finally, to the

vessel in your hands.

Cracked, yes. Imperfect,

certainly. But still holding firm.

It’s still serving its

purpose, albeit differently than when it was whole. The cracks have not

destroyed its utility; they have transformed its character.

This is Australia’s story:

a nation that once hummed with the sound of making things, that knew prosperity

in its most tangible form, that built an identity around the directness of

industrial labour.

That vessel cracked under

the pressure of global competition, technological change, and shifting

paradigms. The cracks widened over decades, sometimes slowly, sometimes with

sudden violence, until the transformation was complete and undeniable.

But the vessel did not

shatter. It adapted. It found new purposes, developed new capabilities,

discovered that some forms of prosperity could emerge precisely where the old

prosperity fractured.

The light now shining

through the cracks is different from the glow of the manufacturing prime, but

it is light nonetheless.

There is beauty in this

imperfection, if we can learn to see it.

Not the false beauty of

pretending the cracks do not exist, nor the nostalgic beauty of wishing for

wholeness that cannot return.

It’s the honest beauty of a

vessel that bears its history, that wears its transformation as a badge of

honour, as a testimony rather than shame, that serves its purpose despite, or

perhaps because of its fractures.

The work ahead is not

restoration but reimagining. Not making the vessel whole again, but finding new

purpose in its fractured state.

Not denying the cracks, but

understanding what light they let through and what that light reveals about

possibility and potential.

Now, as a final exercise:

write down ten great things about Australia in 2025. Then write ten great

things about Australia in 1965.

Which list of 10 things

make you swell with pride the most?

Which 10 things are you

going to file in the trash can?

That act of selection, of

weighing past against present, of deciding what matters most, is the work of

narrative itself.

It is how we decide what

kind of vessel we believe we carry forward.

The vessel is cracked but

the vessel still holds.

These two truths coexist,

and in their coexistence lies the story of resilience, transformation and the

unexpected beauty of imperfection.

This is the vessel we pass

on, fractured but enduring, imperfect but it’s ours, catching the light in ways

that wholeness never could.

My Final Thoughts.

Perhaps what we need now is

not only reflection but resolution.

Imagine a room of patriotic

Australians, the makers, the workers, the educators, the community leaders, the

strategic thinkers, the senior economists etc, all sitting together to draft a

manifesto.

A document that could be

passed on to our policy makers, with a note on it, “We know Australia is a

little broken but we’ve worked out how to fix it!”

A detailed explanation of the

cracks that weakened us and a catalogue of the tools we still hold on the

shores of our island nation that can fix it.

Not just to mend a vessel

that’s cracked, but to coat it in resilience, so that future generations

inherit not fragility but strength.

The vessel is cracked, yes,

but with care, wisdom and good ol’ fashioned Aussie resolve, it can be made not

only to hold, but to endure.

The cracks are our record

of survival; the coating must be our promise of endurance.

Readers Note.

This story is not mine

alone to tell. Every crack in the vessel we call Australia belongs to all of us

and so too must the work of repair.

As you finish with my

article, I invite you to pause and add your own voice: What cracks do you see

most clearly?

What tools do we still hold

to make Australia better?

What protective coating

would you apply to ensure strength for future generations?

If we were to start making things

again, what would the foundation be made from, what’s the magic list of

ingredients we’d need?

The manifesto begins not in

a boardroom, but in the reflections of readers like you. Your answers, your

memories, your hopes, they are the first brushstrokes on the vessel’s new

surface.

For me, I sometimes wish for a time machine, to go back to the 60s, to recapture the spirit of ‘Made In Australia’.

Perhaps there are chapters in our history that hold the keys to our future, as such, what would you bring forward, unchanged or re-imagined, to help the vessel endure?

11. Bibliography.

1) The History of Manufacturing in Australia – Australian Made

2) The Digital Mine: Mining and Technology Innovation in Australia – Minerals Council of Australia

3) Manufacturing in Australia: Past, Present, and Future – Hubner Business Insights

4) Federal Budget May 2024-25: Green Energy & Advanced Manufacturing – King & Wood Mallesons

5) Australia’s Digital Economy Strategy 2030: Paving the Way for Digital Prosperity – Otto IT

6) Australia’s Strategic Blindspot: Deindustrialisation and the Threat to National Resilience – Australian Institute of International Affairs

7) Recession or depression? Australia’s economic insecurity – Defence Connect

8) Structural Change in the Australian Economy – Reserve Bank of Australia, E Connolly

9) Innovating Australia’s Digital Economy – Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

10) Australian Industry Report 2023 – Department of Industry, Science and Resources

11) Australia’s Economic History and Structural Change – Australian Economics Network

12) Deindustrialization and Economic Transition in Australia – Taylor & Francis

13) Australian Economic Development since 1945 – ANU Press

14) Manufacturing Decline and Policy Responses – OECD Reports

15) Australia’s Economic Identity and Globalization – Cambridge University Press

16) A historic guide to Australian car manufacturing – CompareTheMarket

17) Australia’s manufacturing decline and global competition – Manufacturing Global

18) The decline of manufacturing and rise of services – Australian Bureau of Statistics

19) Impact of deindustrialisation on Australian communities – ABC News

20) Renewable energy and advanced manufacturing in Australia – Renew Economy

21) Australia’s evolving economic identity – The Economist

22) Mining sector’s role in Australian economy – Minerals Council of Australia

23) Economic resilience and national security – Policy Forum

24) Australian manufacturing’s economic and social impact – Department of Industry

25) Digital economy shaping Australia’s future – Australian Government Digital Transformation Agency

26) Australia’s economic transformation through globalization – Brookings Institution

27) Service industry growth and economic change – Department of the Treasury

28) Cultural impact of industrial decline in Australia – Cultural Studies Journal

29) Identity and brand narrative of Australia’s economy – Marketing Mag

30) Economic renewal and innovation in Australia – CSIRO Innovation Highlights

[…] […]

I hope that this article reads like a national mirror, one that doesn’t just show us the shine of our past, but the cracks that have shaped who we are today.

The vessel metaphor is powerful because it reminds us that imperfection is not weakness, but history made visible.

I’ve transitioned this story from nostalgia to responsibility: it’s not about longing for the factories of old, but also about asking, “What tools, stories and values do we still hold to build resilience for future generations?

This isn’t just an article about Australian economics, it’s a call to re‑imagine identity, prosperity and purpose.

I hope you find this article as not just a reflection, but an invitation to take part in writing the next chapter of Australia’s story.